Note: This article contains a lot of technical bits, but I’ve done my best to keep the bits small enough so that the article still flows if the bits are skipped over.

So Trump has been in office for a bit over half a year now, and I’ve been involved with FiftyFiftyOneArizona for over half that. I got involved because I volunteered to make this website, but I’ve since been working on other technical projects, most notably a decentralized ICE sighting reporting system, which is still in progress and will be at least until something changes with ICE.

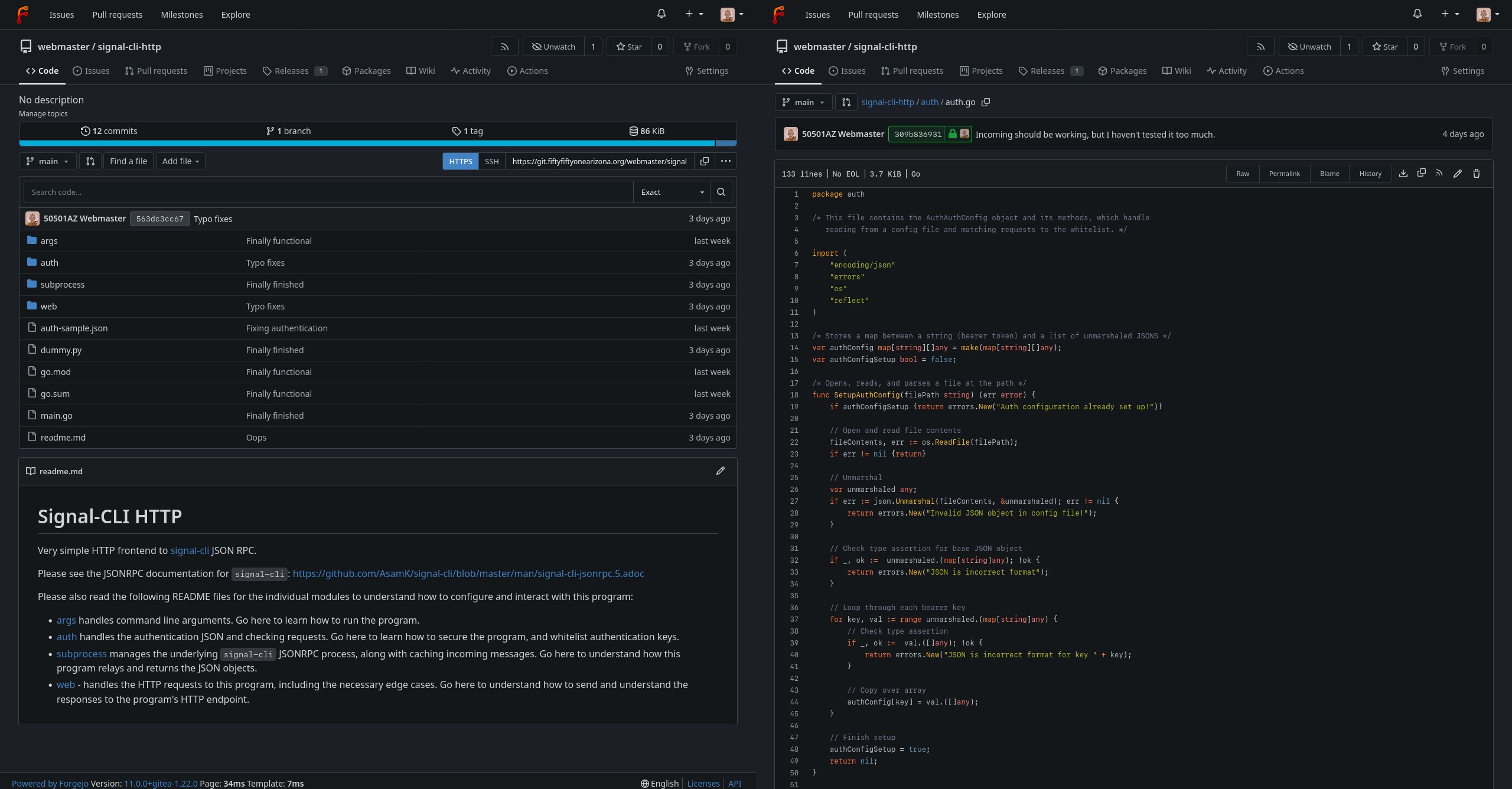

I recently (in this past week) finished a different (but related) project: signal-cli-http. This project was actually created because of the ICE reporting system. I’m at the stage in development of the reporting system where I want to start integrating with Signal, and as I will explain in this article, none of the existing projects for automating Signal worked for my use case.

This article is organized into the following sections:

- My inspiration for making signal-cli-http and the requirements that other projects fail to fulfill.

- The reason I made it in Golang.

- The view from 30,000 feet of how the program works.

My hope for this article is that it will act as a way people can discover this project, potentially decide if they want to use it, and also learn how to use it through examples and the high-level explanation of its functionality.

This article heavily simplifies things. If you want a strictly technical perspective or more detail, please read through the various readme.md files in the project repository.

Inspiration

Signal seems to be the go-to platform for groups like this one (FiftyFiftyOneArizona) to organize. It’s a very reasonable choice. Despite requiring a verified phone number, it is free. And unlike a lot of chat platforms (even end-to-end encrypted ones), it has nearly every single cryptographic feature almost everyone could want. Including deniability, perfect forward and backwards security, and the sealed sender feature ensures that not even Signal can tell who is talking to whom.

I’ve been involved with FiftyFiftyOne Arizona since about April, when I volunteered to build this website. Since then I’ve sort of taken on a role somewhere between tech support and a software engineer. I’ve been doing website building and other odd jobs whenever I’m needed, but my primary focus is making software tools for the resistance. Most notably I have been working on, including the aforementioned ICE sighting reporting system. I made this system for two reasons:

- The fragmentation of ICE sighting reports. When ICE is sighted, the reports are generally forwarded to only one organization, which then puts it up on socials, a website, etc. These organizations tend to only put the reports on one platform. This process is reasonable, but far from ideal. Trump isn’t deporting people. He (or rather his cronies) are kidnapping people and illegally moving them to other countries, and denying them due process. I’m not going to provide sources for that, these are well known facts. As a white guy I’m not that much at risk of being kidnapped. But if I was, I would want to have as much information as possible at my disposal to avoid that, and having to discover these organizations, and individually manage checking them or subscribing to them, potentially on a platform I don’t have an account on, would be a massive barrier to me getting notified of as many reports as I can. In fact, all this is currently a large barrier for adding report sources into my reports system.

- The fragmentation also makes the act of reporting ICE activity more fragile. Instead of the data and reports being distributed like they ideally would be with my system, each organization is separate. If Trump successfully targets one of these systems, there’s little recourse for rebuilding it.

From these two requirements, I decided to use Matrix as a platform to build this on, using Maubot. In order to not add another several paragraphs to this section, I’m not going to explain my reasoning for these choices beyond the following sentence: Matrix is the best-in-class system for distributed, authenticated chat, and Maubot makes writing code for bots easy.

Anyway, my point in the last several paragraphs is to explain the ethos of my development work: I don’t care if what I’m making is feature-friendly, or flashy, or really that easy to use. I am working on mitigating the actions that directly threaten the life, liAll the best,

Benberty, and limb of my neighbors. It just needs to work, and work extremely well.

So I don’t really care that Signal requires a phone number. I don’t care that it is openly hostile towards third-party applications that let me do the integration I want to do. I. Do. Not. Fucking. Care. It’s the best option we have right now, and I have to make it work.

All this is to say: I have a very relevant interest in getting Signal integrated, in some way, with the stuff I’m working on. Or at the very least the ICE reports system. A few weeks ago I set out to do just that.

A few years ago I remember looking into signald, which runs on a computer and can receive commands to do stuff like send & receive messages, manage rooms, etc. Anything that the Signal app can do, this can, but without a GUI. However, this project is unmaintained, and the successor is signal-cli.

I downloaded signal-cli and got it running with an account I set up for FiftyFiftyOne Arizona’s needs. I read through the documentation and messed around with the commands a bit to get a feel for the program.

As I played around with it, I slowly learned that the program doesn’t have any good ways to interact with it for my use case. The program can either be run directly (using two methods) or it can spin up an HTTP server. However, this HTTP server doesn’t have any authentication, meaning any software running on the system I am hosting all this stuff on would be able to do anything to the account(s) logged into signal-cli. That’s kind of bad security practice.

I did a bit more research into alternatives, ideally something with an authenticated HTTP API. I found this repository which adds its own HTTP API, but there’s still no authentication on it, which, for reasons I’ve explained is a must. Someone else made an updated Dockerfile that adds authentication onto it. This seemed reasonable at first, but I decided against it for two reasons:

- Docker is cool and all, but it’s quite a bit of work to learn and maintain. And that’s a bit antithetical to the low-maintenance vibe I’m trying to go for. I don’t want someone to have to learn Docker just to get Signal working.

- The authentication doesn’t have any way to have multiple logins to isolate permissions to certain rooms, contacts, etc. So while only software I allow could access Signal, any program I allow would have full access. This also doesn’t really fit with the low-maintenance vibe. Everyone makes mistakes. And even if I didn’t, other people do. And I want more people to get involved with this kind of work, and it would be very nice if a security flaw in a script or program couldn’t damage anything that isn’t absolutely necessary to allow for that program.

I looked around a bit more and it was clear to me that there wasn’t a single project that suited my need for granular authentication. I decided I must make my own.

So, Why Golang?

It’s easy to program in. It is literally designed to be as well. There’s a good quote explaining exactly why here.

Python is cool and all, but it’s far from ideal for a program whose entire purpose is to provide secure, robust authentication. While Python is memory safe, nothing is statically typed, leading to development headaches for large programs. I think it’s fine that I’m using it for the Maubot plugins because the code is rather short, most of it is shared from the Maubot source itself, and each plugin is isolated from one another (reasonably).

Before writing any code, I had a very good idea of how the program would work. I wasn’t going to proxy the HTTP endpoint, because doing so would just expose the unauthenticated endpoint anyway. I knew that I would have to run signal-cli as a subprocess and parse the terminal output from it.

Golang is separated into modules, and medium-sized pieces of a program split very well into these modules when it comes time to actually write the code. I knew I would need a module for calling the subprocess, and another for the HTTP server, which would translate the HTTP requests and responses for the subprocess module.

The View From 30,000 Feet

It wasn’t actually that hard to make. Like I said in the previous section: I knew exactly the modules I would have to make. It took me less than a week to do in its entirety. On top of the main.go file, which simply orchestrates the modules, I built it with four modules:

- args handles command line arguments. Stuff like where the signal-cli program is, what port to listen on, etc.

- auth handles the authentication JSON and checking requests. More about this later

- subprocess manages running signal-cli as a subprocess

- web – handles the HTTP requests to this program, including the necessary edge cases including authentication, and badly formatted requests

I originally intended to make a typical REST API – a type of API where each action has its own endpoint and JSON request schema. This was reasonable, but it would require that I implement not just the code, but also the JSON schema for every individual action. Not to mention how much testing I would have to do to check that I didn’t make a mistake, which is against my need to work fast.

I took a step back and tried to come up with a different way. And I discovered the perfect thing – JSONRPC.

I’m not going to explain what this is in too much detail partially because I don’t understand the system in detail (and don’t need to!). In fact, making the program on top of this system is so intuitive I’m not even going to explain what this JSONRPC thing is at all. I’m just going to give you an example of how the program would handle an incoming HTTP request:

- Within the HTTP module, the program would check that there is a body sent along with the request and that this body is a valid JSON object. There’s no reason for a request to not include a JSON in some way so this is a must.

- The auth module is used to check the Authentication header and the request JSON object against its authentication configuration. It responds with a 403 if it’s not allowed.

- The subprocess module then forwards the request to signal-cli, that is, it pastes the request JSON object string directly into signal-cli’s STDIN (this is where you can type text into a program run by a command line, not to be confused with the command line arguments.

- The subprocess module then waits for the signal-cli process to return a JSON for the request. Once the response comes in the HTTP module takes back over.

- The HTTP module returns the JSON that the program spit back out.

I’m heavily simplifying here. There’s a completely different process involving a cache for handling incoming messages (from different contacts or other devices). Again, if you want a more detailed view look through the documentation in the repository.

The takeaway from this section is that: the program doesn’t have any understanding of what it’s doing. It simply forwards requests into the JSON-RPC system, and returns the result. It doesn’t understand what a request means, nor does it need to. It’s up to whoever sets up and uses the program to configure it to make it do what they want.

There’s also the authentication system. I’ve tried multiple times to explain it but I’ve found that it’s impossible to do so without basically copy-pasting the documentation for it. Basically, the authentication works as follows:

- Each HTTP request must come with a header that contains a bearer token.

- The program is configured to read from a file that defines, for any given bearer token, a set of “match” JSON objects that each request bearing that token is checked against.

- A JSON in a request can match to one of these “match” JSON objects if it is equal to or more specific to said object. For example, one of the “match” JSON objects says “send to <group>”, it will allow the bearer token to send any data (text, image, etc.) to that group.

This authentication system works similarly to the subprocess system. It is completely blind to what’s happening. It only checks that, for a given authentication bearer token, the JSON object in the request is the same as or more specific to a JSON object that the program is configured to accept for that bearer token.

Conclusion

This article turned out to be a bit longer than I anticipated and wanted. Although I am happy with the level of technical detail it has. I hope that, if you’re someone like me who would benefit from this program, you have learned about it and can now use it.

If you are someone who wants to help with the stuff I am working on, my contact details can be found by clicking my name at the top of this article.